The last time I spoke to my youngest brother Peter was on his 31st birthday. Six times, I had tried to get through, but each time the phone connection dropped out. Finally, on the seventh attempt, it went through.

I was at my home in McLean, Virginia. He was in a locked ward in a psychiatric hospital in Sydney half a world away. I recall feeling like I had a stone in the bottom of my stomach as the words “happy birthday, Peter” left my mouth. There was so little about his circumstances that were happy. Not only was he suffering from a terrible illness, but this was not the first birthday he had spent in a psychiatric ward. He’d woken up in a hospital on his 21st birthday, too.

In the 10 years that had passed, Peter had developed a severe case of paranoid schizophrenia. While there were times when he wasn’t doing so badly, over the years they grew shorter and further in between. Each time he descended into tormented madness, he never quite got back to his former self.

All the while, the dreams and ambitions that my athletic, quick-witted, handsome brother Pete had held for his life gradually disappeared, replaced with despair, shame, paranoia and, ultimately, hopelessness. I’ve often thought how glad I was that back in 1999, when Pete went psychotic for the first time, that none of us knew what lay ahead. I don’t think any of us—my mum or dad or five other brothers and sisters—could have coped knowing the agonizing heartache and absolute anguish that was to follow.

When Peter took his life on April 2, 2010, it was because he had given up any hope that life would ever get better. While none of us liked to admit it, we all had. Any effectiveness his medications had to quiet the demons that tormented him day and night had long seemed to disappear. A former all-star athlete, the medications had contributed to him putting on a lot of extra weight and losing his former agility. His speech, reactions and movements had all slowed, and while he never quite lost his sense of humor, the moments in which he found any lightness had grown few and far between.

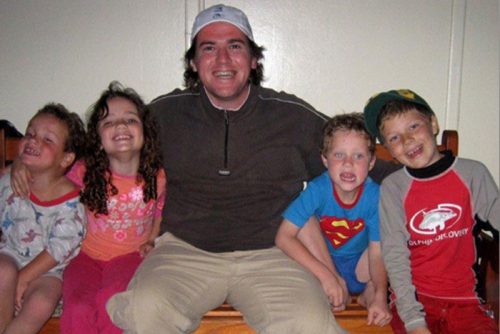

As I spoke to Peter that last time, he asked about my kids. He always loved to hear how they were doing, particularly my oldest son Lachlan, who, like Pete, was passionate about basketball and in awe of his uncle’s ability to spin a ball on the end of his finger. Peter loved doing that trick for Lachlan. It was one of the few talents he never lost, though he knew he’d never be a star on the court again. In his lucid moments, he was acutely aware of the giant chasm between the life he was living and the life he’d once dreamed about. Seeing old schoolmates and friends was too painful, so he hid himself away, shame and humiliation his most constant companions.

MY BROTHER PETER WITH MY FOUR KIDS

While Peter wasn’t always easy to love during his illness, he was always, always, so loved by his family. He was living with my sister, her husband and their three children when he decided to take his leave of this world, and while we all grieved his death, what we grieved most of all was the life he never got to live. The one comfort we had was that Peter no longer suffered, that at last, in death, his mind could find the peace that had grown so elusive in his living. We also knew that he always knew we’d never stopped loving him, even when he was at his most unlovable.

On hearing the news that iconic fashion designer Kate Spade had taken her life last week, my heart hurt—for her, and for her family who loved her. Then, three days later, hearing that Anthony Bourdain had also taken his life, my heart sank yet again. I can only imagine the darkness that had descended over both of them in the hours leading up to their final decision. So much darkness. Too much darkness.

While I don’t have all the answers to curing the rise and rise of suicide and mental illness in our world today, I am certain that removing the stigma that surrounds it would help to ease the suffering of those who are struggling and make it easier for them to reach out for help when they need it.

Mental illness carries so much stigma. Too much stigma. While there is no shame taking time off work after a bout of pneumonia, sharing that you have a mental illness is an act of profound courage for the risk of rejection, judgment and discrimination people are afraid they’ll face. Just imagine if people felt as comfortable talking about their anxiety, bipolar disorder or PTSD as they do talking about their tendinitis or high cholesterol. Not only would removing the stigma markedly reduce the suffering of those who are dealing with mental health, but it will help those who are caring for them to respond with greater courage, compassion and resilience.

Sharing Peter’s struggle with paranoid schizophrenia has made me incredibly compassionate toward all who suffer from any mental illness. Compassionate also for those who try to support them. It is a heavy cross for all.

Data shows that one in five adults are suffering from mental illness and that suicide rates in the U.S. have risen 30 percent over the last 20 years. So as you read this now, chances are you’ll know at least one person who is dealing with some form of mental illness. That being the case, each and every one of us has an opportunity to help remove the stigma surrounding it and lower the barriers for people to get help.

There are many ways we can help to destigmatize mental illness and make it easier for people not to self-stigmatize themselves. Talk openly—without shame or self-consciousness—about your experience of depression, anxiety or other mental illness. If you sense someone around you may be struggling, have the courage to ask them how they’re doing. Put yourself in their shoes and imagine how they’re experiencing life. And if you are struggling yourself, I encourage you to reach out and give people the opportunity to support you (this is a gift to them, not a burden) and to keep faith that hope exists no matter how dark life may feel right now. Because it does. Rediscovering it is easier when we let others in and don’t go it alone.

If you or someone you know needs help, please contact your local Suicide Prevention Lifeline or a mental health care agency or professional.